What the most sophisticated bomber says about business strategy

The Boeing B-29 Superfortress was vastly more complex than aircraft that came before. Getting it into production required not only a plan, but a whole new way of thinking for business strategy.

On 11 January 1944 General Henry “Hap” Arnold, the head of the US Army Air Forces, arrived at the vast Boeing factory at Wichita in Kansas. The assignment for the 57-year-old, who had learned to fly at the hands of the Wright brothers in 1911 and became one of the first military pilots in the world, was to get production of the B-29 Superfortress bomber back on track.

The Superfortress, the aircraft that would eventually carry atomic bombs to Japan in August of 1945, was a revolution in aircraft design. It featured cabin pressurisation, to allow its crew to fly in comfort at high altitude, analogue computers to enable remote operation for its defensive weaponry, and a broad range of other technology that was ground-breaking for the time. It was also phenomenally expensive — at $3bn the Superfortress programme that delivered the atomic bombs to Japan cost more than the $2 billion Manhattan Project that built the bombs themselves.

By January 1944 the B-29 programme was also in crisis.

Under the pressures of wartime, and lacking any other bomber that could reach Japan from existing US bases, Boeing had moved the plane to mass production before a series of glitches were successfully sorted out, in particular with the engines. The purchase order for 1,664 B-29s was placed before the first prototype had flown. By January 1944 the Wichita plant had built 97 Superfortresses, but only 16 were in flyable conditions. When General Arnold arrived, most were stuck at ‘modification centres’ to iron out defects.

Arnold was under enormous pressure to bomb Japan. Throughout the second half of 1943, US President Franklin Roosevelt badgered General George Marshall, the overall US Army chief of staff — and Arnold directly — about progress with the B-29. Yet all the president seemed to hear were delays and problems. “We are falling down in our promises every single time,” Roosevelt told Marshall in October. “We have not fulfilled business strategy yet.” The next month, however, at a conference in Cairo, Roosevelt promised Chinese leader Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek that B-29s based in China would bomb Japan by the spring of 1944.

They now had to get the plane to work. Yet, as both Roosevelt and Arnold were finding out, there is a difference between having a plan and executing it. In a situation of multiple priorities, the interim target of getting the new aircraft built had obscured the more significant objective of getting it to fly. General Arnold needed to focus on the benefit the US could achieve from its new wonder plane — bombing Japan. Instead, initially, he focused on a superficially appealing but ultimately futile interim goal — getting airframes off the production line.

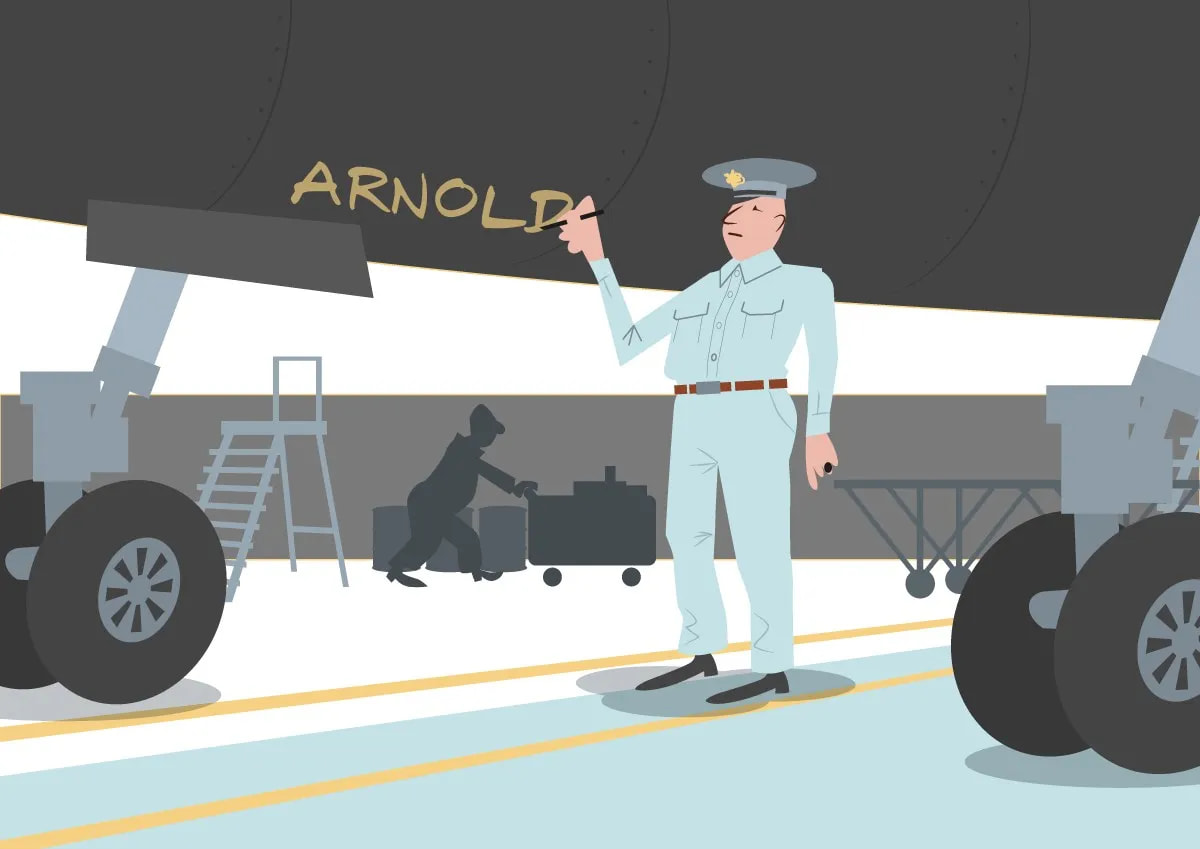

Arnold wanted 175 aircraft for initial operations against Japan. On his January visit he walked down the Wichita line, selected the 175th B-29, and wrote his name on it. He said he wanted it delivered before 1 March 1944. Arnold had given the manufacturer a clear line of sight. However, there was still a failure to focus on the overall business strategy. Boeing met that initial demand; the specified aircraft rolled out on 21 February. But broader production was still troubled. When Arnold returning to Wichita on 9 March, the general found that there were still no B-29s actually ready to fly in combat. Some had been sitting waiting for parts for more than two months.

Now Arnold was livid. In their attempt to build the most sophisticated bomber that the world had ever seen, he, the USAAF and Boeing had lost sight of the primary requirement that any military aircraft must have — to actually be able to fly. “The program was void of organization, management and leadership,” Arnold wrote in a blistering memo on March 20. “The situation as I found it was a disgrace to the Army Air Forces.”

At Wichita, in the depths of a freezing winter, the general instituted a revolution. Arnold had a formidable temper when he needed it, and that helped matters to move along. But more pragmatically, he helped the organization see what actually needed to be done. He focused on benefits, getting an operationally capable aircraft into the air, not just rolling airframes off the production line with myriad faults that rendered them impossible to use.

Arnold also did not work alone. He appointed Brigadier General Bennett Meyers as ‘special project co-ordinator.’ Meyers, in the words of a former director of the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC, “imposed order on the chaotic programme.” Boeing sent an additional 600 workers to Wichita. USAAF units contributed their best maintenance staff. Subcontractors prioritised deliveries for the B-29. Much of the work on aircraft was outside, interrupted by snowfalls. Sometimes it was so cold that staff could only work for 20 minutes before going to warm themselves at heaters.

The new effort made thousands of changes to the aircraft, from strengthening internal structures with steel plates to upgrading electrical connectors and adding new rudders. They changed flying techniques too, delaying climb after take-off to reduce engine overheating. Most significantly though, Meyers’ teams carefully monitored the changes they were implementing. It was not enough just to make a series of ad hoc fixes on the production line to get an individual B-29 flyable; or even just the first 175 airframes. They needed to institute a method that could tame the fiendishly complex new aircraft for mass production, and stay that way for the duration of the war.

This project, later known as the ‘Battle of Kansas’, worked. After five weeks the first combat-ready B-29s left Wichita for US bases in China, to commence bombing Japan. Refinements continued constantly throughout the life of the aircraft. Likewise, the capture of the Marianas Islands from June 1944 onwards provided bases more practical than those in China, which were at the limit of the B-29’s range. But the blockage was cleared.

The morality of the subsequent firebombing of Japanese cities in the spring of 1945, and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August of that year — both undertakings for which the B-29 was pivotal — is still hotly disputed. However, almost 80 years on, Hap Arnold and Bennett Meyers’ management at Wichita is nonetheless testament to the need, when trying to achieve a formidably complex goal, to not only formulate a business strategy, but also to have a system in place to make sure you are actually executing it.

Arnold was rewarded for his labours. In 1949, by act of congress, he received permanent five-star rank as a general of the new United States Air Force, the first (and last) such commission ever granted. (By contrast, Bennett E. Meyers, Arnold’s hard-charging deputy in Kansas in 1944, was convicted in 1948 for profiteering from aircraft procurement in the war; he was dismissed from service, and saw his medals stripped away. His wife divorced him, and he lost his 12-room Georgian colonial home on Long Island).

Among the documents relating to the Superfortress in US Air Force archives there is a text with brown covers titled, “Construction and Production Analysis — Boeing-Seattle — B-29.” Dating from 1946, the paper is “a determination of the means required for a rapid expansion of aircraft production in the event of a future emergency.” A year after the end of the war, the US military looked back to see what had worked and what had not in the titanic effort to get the bomber into service. That was a sensible retrospective approach, given the methods available at the time. However, if it had existed in 1944, Hap Arnold could have used a piece of software for strategy execution management to assess the implementation of his business strategy plans in real time. Just like the DecideAct solution, see how!

In my next piece I’ll be discussing why companies also can get sick.

PS: We are a very friendly company from Denmark and do not support the use of lethal weapons. This story has been used as an example from history.

Flemming Videriksen has been a trusted strategic advisor and executive coach for top leaders in businesses and organizations worldwide for over 25 years. He is now the CEO and founder of DecideAct, which aims to deliver intelligent digital solutions to support leadership and management to succeed in their execution of strategy.