Companies get sick too in a business crisis

In a crisis it’s not enough to have a plan — you need to know how to execute it as well

Since the beginning of the pandemic, coronavirus has turned the world upside down. Covid-19 cost human lives, but its effects on businesses have also been profound. Just as people get sick, so in covid times do companies. In the US in 2020, 630 relatively large firms — defined as public companies with assets or liabilities of at least $2m, or private companies with at least $10m of the same — went bankrupt. That was an increase of 9% from the year before and the highest level of annual bankruptcies for a decade.

In the UK a study in January this year found that more than one in seven British businesses — employing 2.5 million people and providing 9% of the country’s employment — were at risk of failure by April. ‘Micro enterprises’ with under ten employees were particularly vulnerable to closure. In March the British government extended temporary insolvency measures for another three months.

Across the world whole sectors particularly impacted by covid regulations, such as hospitality and the performing arts, now face an existential business crisis.

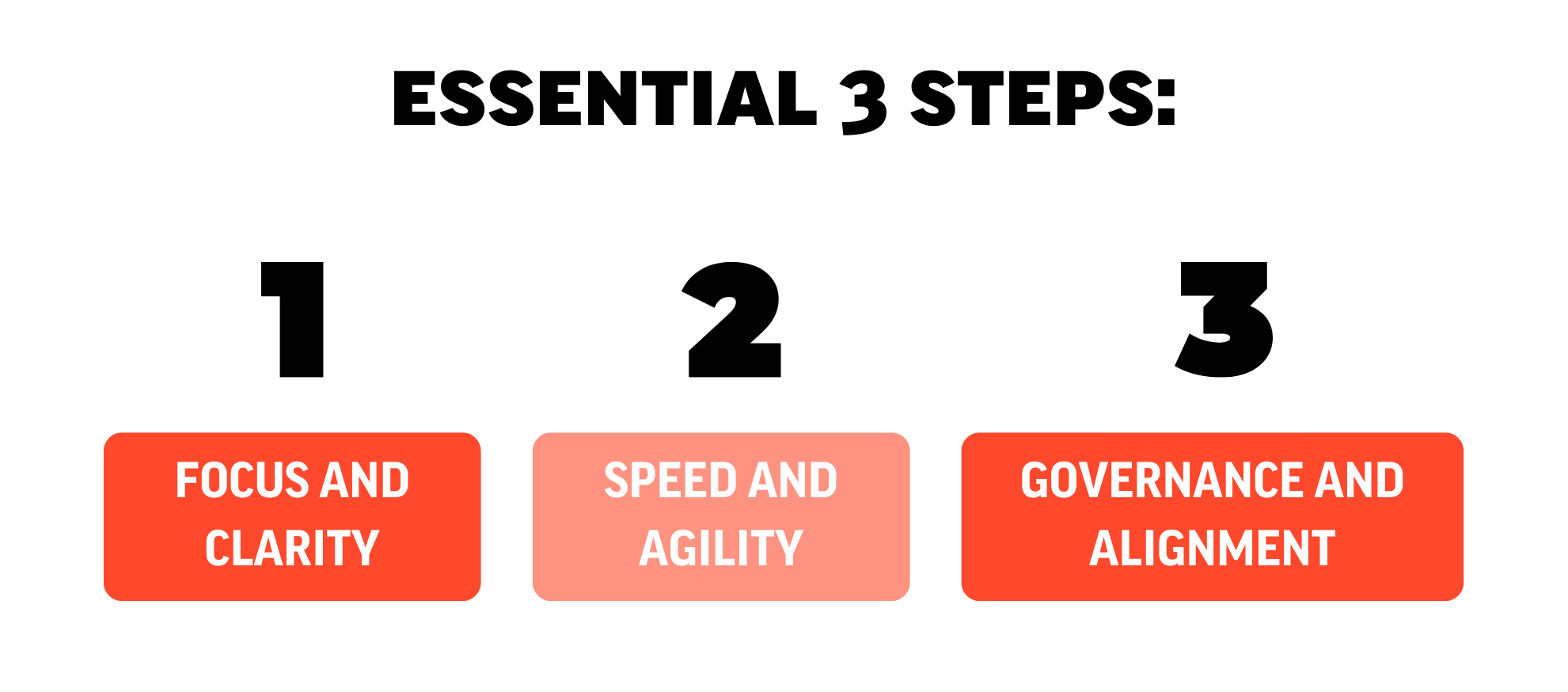

In situations like a business crisis, it is not enough just to make a plan. It is equally important to execute that strategy properly, and to monitor the process in as close to real time as possible. While in the past the way to do that might have been via nothing more sophisticated than a CEO’s notebook, today there are technological tools that can assist. In, so doing, it is possible to find both quick wins and long-term benefits.

Companies, like the human body, are made up of constituent sub-systems. In times of business crisis these sub-systems will not all be equally impacted. For instance, it is a widely repeated truism that during the lockdowns implemented to combat covid-19, online businesses boomed while brick and mortar traders, in particular retailers, faced annihilation. But that division does not neatly divide all institutions. For instance, the British retail chain John Lewis announced in July last year the permanent closure of eight of its 50 stores, and began redundancy talks with 1,300 staff. Overall in 2020 the firm lost £517 million, and failed to pay its staff a bonus for the first time in 67 years. Pain continued this year, with another 1500 head office jobs cut. Yet at the start of the covid lockdown John Lewis’ online sales were higher than at Christmas, usually it's busiest time of year. Meanwhile, in the US Walmart also saw an online boom — with sales there nearly doubling in the second quarter of 2020 — but also a parallel rise in in-store shopping. Overall in 2020 Walmart’s revenues jumped $35 billion, up 6.7%. The primary reason for this discrepancy is that Walmart sells food, demand for which is more consistent in a pandemic than John Lewis’ main department store offerings of furnishings and clothing.

Other firms that pivoted quickly at the start of the pandemic include Uber, which introduced new services to transport goods, not people or meals. Elsewhere Melitta used its knowledge around coffee filters to produce face masks; General Motors and Ford were encouraged by the government to manufacture ventilators.

It is important to use any business crisis situation as an opportunity to build excellence in strategy execution and bring strategy to the core of the organization. Those who sharpen their ability to execute and adjust strategies in an instant and agile way will have far better chances of survival and success.

As a report from management consultants Kearney summarised: “What the pandemic did for Uber, Ford, General Motors, the airlines, and dozens of other companies was let them redeploy physical assets by focusing on how they make things, rather than exclusively on what they make. The true power of strategic deconstruction was tapped by moving past physical process into purpose-based activities.”

As with individual recovery from illness, the objective for a company when emerging from a business crisis should not be just to stop being ill, but rather to come back stronger. It is easy, when the immediate emergency has passed, for an institution to drift. In Iceland, a number of businesses congratulated themselves on weathering the immediate economic downturn after the 2008 financial crisis — which took down Icelandic banks with total assets of $155bn — only to succumb to a slow decline over the longer period that followed.

By contrast, Reykjavik Energy (RE), the world’s largest producer of geothermal energy, and likewise in crisis post-2008, was able to stay on track. They initially developed a five-year plan that became the focus of everything that followed. It was simply called “THE PLAN”; everyone knew it and could relate to it. They rebuilt the entire leadership team, worked to align core values with regular measurements, and gave all units of the company ownership of the strategy. RE achieved all the goals of the five-year plan within four years.

The problem — given the scale and complexity of modern organisations — is really one of monitoring. Enterprise Resource Planning software today provide CEOs and shareholders with real-time data on the financial underpinnings of a company. They can see everything, from cash flow to inventory levels. For strategy matters are much more primitive. Those scribbled notes in a CEO’s notebook are often the only monitoring machinery that exists. The problem is a failure to acknowledge that, as with any other business function, strategy requires an operational backend to monitor and implement, just as trading or procurement does. Otherwise matters do not stay on track.

Examples of corporate strategies devised at great cost and then failed to be implemented properly are numerous. In the 1960s and ’70s the Schlitz Brewing Company, one of American’s most famous beer makers, aimed to increase the speed-to-market and profitability of its product. However, the measures they took, first incrementally replacing barley malt with corn syrup, hoping that consumers would not notice as the changes took place, and later cutting brewing time from 25 to 15 days, produced a beer that tasted appalling and was lined with sediment, comparable to mucous.

On a national scale, before the current coronavirus pandemic Western governments had also spent substantial sums drawing up plans for a response to pandemic influenza. Yet with the Europe-wide rush to lockdown March 2020 those pandemic plans — which focused on ‘flattening the curve,’ rather than trying to suppress infections entirely, went out of the window. This week Dominic Cummings, who served as prime minister Boris Johnson’s chief advisor until his ousting in November last year, gave a searing account to a parliamentary committee of apparent chaos and panic inside the British government in London at the start of the pandemic. In Cummings’ telling, on 13 March 2020 a senior civil servant came to see him to say the initial government plan would not work, and they would need a “Plan B”. Apparently she said: “We’re going to have to ditch the whole plan and we’re heading for the biggest disaster this country has seen since 1940. I’ve been told for years that there’s a whole plan for this, (but) there is no plan, we’re in huge trouble. I think we’re absolutely f****d and we’re going to kill thousands of people.” Whether that was a sensible response to changing events, or a hurried move that replaced a policy that, however imperfect, did have an exit strategy with a series of panicked short-term actions, is likely to be debated for years. Much will depend on whether the initial success of vaccination roll-outs can be maintained in the face of new variants and those who are reluctant to receive a covid jab.

Some means to keep strategy on track are structural to a business crisis. It is wise for businesses to establish Strategic Governance Committees to oversee implementation in the same way that another committee might oversee capital expenditure. Likewise, the position of Chief Strategy Officer should be as standard as that as a CFO or COO. As ever with staffing, choosing the right personalities and ensuring that the committee has sufficient power is crucial. Lower down the corporate hierarchy, there is merit in reducing or eliminating job descriptions in pursuit of greater agility — that allows individuals to focus on outcomes (benefits) and not on processes.

But there is also a role here for technology. The product our firm has developed, DecideAct, provides a cloud-based, real-time dashboard for Strategy Execution Management for firms of any size. It lets business leaders actually transform strategy into action. A simple interface shows progress towards certain defined goals, and indicates where problems have occurred. As mentioned above, such platforms are now standard ways to manage many business processes — from logistics to manufacture — with much greater efficiently. The opportunity here is to have the same gain with strategy. Book a demo and see how DecideAct will help your strategy see the light of day in times of business crisis.

The introduction of new software tools takes time and effort. Business leaders are understandably sometimes wary of doing so. But, given the striking difference today in the tools and level of sophistication firms use to manage manufacturing and logistical processes compared with their strategy implementation, it is time to bring the latter up to speed. We should retire the CEO’s notebook for good.

If you can’t afford to lose another strategy in implementation, it’s time to take strategy execution seriously. Make it the core of the organization and implement modern tools to drive execution and follow-ups and deploy an effective recovery strategy.

There is more than one way to implement your recovery plan, but it is essential that you remain consistent: keep trying, and if necessary, fail fast, then reshape your plans. But to succeed, you need a structured approach, a very tangible plan and instant and transparent follow-up.

Flemming Videriksen has been a trusted strategic advisor and executive coach for top leaders in businesses and organisations worldwide for over 25 years. He is now the CEO and founder of DecideAct, which aims to deliver intelligent digital solutions to support leadership and management to succeed in their execution of strategy.

%20(1).png?width=596&name=DECIDE%20ACT-06%20(2)%20(1).png)

.png?width=596&name=New%20Strategy%20Execution%20(1).png)